Pick A T - Public Campaign to Promote the Use of Toothpicks: A Pilot Study- Juniper Publishers

Juniper Publishers- Open Access Journal of Dentistry & Oral Health

Abstract

Introduction: Caries and periodontal diseases, as most common oral diseases, can be prevented by performing optimal oral self-care, which means daily adequate tooth brushing, including inter dental cleaning, for example the use of toothpicks.

Objectives: Two Pick a T pilot field studies were set up, aimed to evaluate relatively innovative implementations of monitored oral hygiene activities in the HORECA (Hotel, Restaurant and Catering).

Material and Methods: The first study was conducted in three restaurants; single wrapped toothpicks were presented passively or actively to the customers. The second study was conducted in a foodmarket; 290 customers received toothpicks with Aminfluoride after they completed a questionnaire (T1). Additionally, for a follow-up study (T2), an e-mail address was requested. 146 respondents received a digital questionnaire, including original items preceded by the introduction, 'in comparison to the last time that you filled in the first questionnaire and received the small box of toothpicks'.

Results: In the restaurant -in which toothpicks were offered by active and passive approach-, in one day, after the toothpicks were distributed actively, 203 single wrapped toothpicks were taken. From the table boxes, 92 toothpicks were taken actively, and in the passive approach situation,160 toothpicks were taken by the customers. In the two restaurants, where toothpicks were only offered by a passive approach, 370 toothpicks and 150 toothpicks were taken. In the second study the customers reported to use toothpicks at least once a day (T1: 15.2%, T2: 28.9%), and they valued the use of a toothpick after eating as important for a fresh mouth feeling and optimal oral health. In general, the use of toothpicks in the HORECA was valued as very important too. Conclusions: Providing of toothpicks in the HORECA was not only much appreciated by the managers and the costumers, it also seems to encourage their interdental oral self-care.

Keywords: Behavioral sciences; Public health; Oral health promotion; Oral self-care; Toothpicks; The Netherlands .

Introduction

Most common oral diseases -caries and periodontal diseases- can be prevented by performing daily optimal oral self-care, and oral health professionals agree that adequate tooth brushing, including interdental cleaning, for example the use of toothpicks, interdental brushes or floss, and tongue cleaning is essential for prevention [1,2]. Moreover, preventing oral diseases is due to oral health promotion efforts and success of dental public health promotion initiatives, that specify and target beliefs, intentions and context-related behaviour change [3,4]. However, health behavioral change is complex, and even when preventive oral health self care interventions are implemented individually, at schools or workplaces and provided by oral health professionals, people often are not well informed and don't perform the appropriate behaviour [5]. The well-known expression of folk- wisdom: 'young learned, old done” may be true. Studies show that only early childhood caries can be successfully prevented by population-based preventive programmes via aiming at the change in behavior. However, effects of individual tailored motivational/informational interventions has not yet been clearly demonstrated, neither for the prevention of caries nor for periodontal diseases [6]. Besides, it is quite unfortunate, because in the literature effect studies related to dental public health or expected behavioral changes related to an oral health campaign are hardly found [7].

Nowadays, oral health is considered as a multi-faceted phenomenon, including the ability to speak, smile, smell, taste, touch, chew, and swallow, as well as the ability to express a range of emotions through facial expressions with confidence and without pain, discomfort and disease of the craniofacial complex. Moreover, oral health is influenced by the values and attitudes of individuals and communities, and reflects the physiological, social and psychological attributes that are essential to the quality of life. Additionally, oral health is influenced by the individual's changing experiences, perceptions, expectations and ability to adapt to circumstances [8,9]. Oral diseases are significant public health issues worldwide, and it is of great importance to integrate oral health not only into global health agenda, but also via the common daily life approach and through effective multidisciplinary and society collaborations [10].

From social psychological perspective, it is becoming increasingly appreciated that the way oral diseases affects, and the impact of oral self-care has on people's lives are just as important as epidemiological measures of its prevalence or incidence. Historical noteworthy, a (in)direct oral health related motivational initiative in combination with a incentive (free providing toothpicks) has been shown to lead to effective -short term- behavior change. Namely, it was around 1870 that Charles Forster had introduced toothpicks into restaurants. Commissioned by Forster, Harvard students demanded wooden toothpicks after they had finished dining on Forster's dime at a local establishment. The Harvard students vowed never to eat at the dime again, when no toothpicks were available. Then, on Forster's suggestion, some days later the restaurant manager distributed toothpicks to his customers. In earlier years the toothpicks had a further use, because besides the availability ofwooden toothpicks in restaurants and the use ofthem for their intended purpose: Chewing toothpicks in public became fashionable, especially among well-to-do men and young women. Noteworthy, chewing a toothpick became a sign of contentment and insouciance [11]. Nowadays chewing a toothpick seems not to have similar connotation, but given the potential advantages of the toothpicks, including the contemporary emphasize on promoting oral health, and may be as a possible substitute for the manipulative component of the smoking act in a quit smoking intervention [12], it could make a comeback?

There are various toothpicks available in all sizes and forms, round or triangle, wooden or plastic with several tastes. From professionals point of view the wooden triangle single wrapped toothpick is the best toothpick to get in the HORECA. Could HORECA managers, in line with the initiative of Charles Forster, distribute the wooden triangle single wrapped toothpicks to their customers to stimulate them to use professional toothpicks after dining?

These two pilot Pick a T field studies were set up, aimed to promote the awareness of oral health and to evaluate relatively innovative implementations of monitored oral hygiene activities, such as the use of a toothpick in the HORECA.

Materials and Methods

In 2014 the first Pick a T study was conducted in 3 restaurants in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Restaurant 1: Brasserie Flo is located in the center of the city, and this restaurant specializes in classic French cuisine and has seats for 78 customers. Restaurant 2: Eethuis de Jordaan is located in the Jordaan district, and it is a shoarma and grill restaurant, where customers can have diner inside or could choose for a take away option. Restaurant 3: Maximus Steakhouse is located in the center of Amsterdam too, and this restaurant has seats for more than 100 customers; additionally there is a terrace outside with space for another 80 guests.

Single wrapped and/or table boxes of wooden triangle toothpicks were distributed (standard procedure) passively or actively to the customers. The sort of approach -passively or actively- was tailored to, or was set up depending of the formula of the HORECA organisation. In restaurants Brasserie Flo and Eetcafe de Jordaan the single wrapped wooden toothpicks were only distributed passively. In restaurant Maximus Steakhouse the single wrapped wooden toothpicks were distributed passively and actively.

The passive approach involved the situation that existing cocktail picks (round and two-ended points) were being exchanged into single wrapped wooden triangle toothpicks, and the toothpicks were provided in the bathroom, near the entrance and at the dining tables. At the cash desk, toothpicks were provided by customers by asking the waiter directly or by helping themselves. The active approach involved the situation that toothpicks were included when the customers received the bill. At the end of every day or period (depending of the sort of approach) the number of toothpicks that were taken by the customers was counted by the investigators.

In 2015, the second Pick a T study was conducted in a foodmarket the Foodhallen in Amsterdam. 290 customers received a box of toothpicks with Aminfluoride after they had completed a questionnaire (T1), including statements that were measured on a 4-point Likert-scale. Customers' perceived oral health was measured by the 'Ladder Scale' as the Self-Anchoring Striving Scale [12]. By providing the toothpicks as a reward for their participation in the study, the customers were encouraged to use this interdental tool directly. In addition, an e-mail address was requested for a follow-up study (T2). Three weeks after T1, 146 respondents received a digital questionnaire, including original items of T1 preceded by the introduction, 'in comparison to the last time that you filled in the first questionnaire and received the small box of toothpicks'.

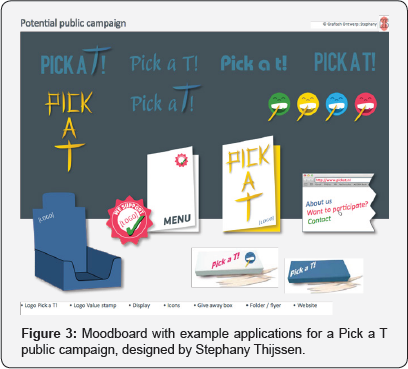

To increase the awareness of oral health by promoting the use of toothpicks in context-related behaviour change circumstances, other than in regular dental services, a specific Pick a T logo was developed by a professional grafic designer (Figures 1 & 2).

Results

Findings in the first Pick a T study (2014) show that in restaurant Maximus Steakhouse, in which toothpicks were offered by active and passive approach over several days, a total number of 295 toothpicks were taken when the toothpicks were distributed actively; in one day 203 single wrapped toothpicks were taken, and at the next day 92 toothpicks were taken actively from the table boxes. From the passive approach, in restaurant Maximus Steakhouse in total a number of 210 toothpicks were taken by customers. In restaurant Eetcafe de Jordaan and in restaurant Brasserie Flo, where toothpicks were only offered by a passive approach, in 5 days in total 370 toothpicks (210 from the tables and 160 from the desk), and in 4 days a number of 150 toothpicks were taken (101 from the restrooms, 39 from the entrance table and 17 from the stations), respectively.

In the second Pick a T study (2015) findings show that at T1, the average age of 290 customers was 38.4 years (SD= 16.8), and at T2 (N =38) the mean age was 45 years (SD = 18.7). Customers' educational level was advanced vocational training up to higher professional education. At T1, 35.5% of the customers had never been to an oral hygienist, and at T2, 5.3% intended to make an appointment with an oral hygienist.

At both measurements customers' perceived oral health was valued as 'good', T1: M =7.8 (SD = 1.1) and T2: M =7.7(SD = 1). The customers reported to use toothpicks not every day (T1: 49.3%, T2: 44.7%) or at least once a day (T1: 15.2%, T2: 28.9%). Similar percentages of customers (T1: 66.2%, T2: 68%) valued the use of a toothpick after eating as (very) important for a fresh mouth feeling and optimal oral health. Two third of the customers (T1: 65%, T2: 65.8%) valued the use of toothpicks in the HORECA as (very) important too.

Conclusion

Firstly, the owners/managers of the three restaurants in the first Pick a T study responded very positive towards the different approaches of distributing toothpicks among their customers. In addition, they all were able to distribute the toothpicks in the way as the approach suggested, thus passively or actively. The waiters who offered the customer the single wrapped wooden triangle toothpicks noticed this option as an extra service to their customers. The number of used single wrapped wooden toothpicks shows that customers appreciate the provided professional toothpicks. Secondly, because this Pick a T initiative is a pretty new market, its success depends on the conscious, beliefs and attitude toward the use of tooth picks of the HORECA owners/ managers. For the replacement market (i.e., the change of existing cocktail picks into single wrapped wooden triangle toothpicks) an adequate persuasive oral health communication is needed. For instance, Figure 3 is a moodboard with example applications for contributing to public health for a Pick a T public campaign or a promotion of the use of tooth picks in daily life (social norm). A few points of concerns are important, if Pick a T is being continued as a public intervention; an active approach is preferable due to direct e and cost-effective although, it depends on prize- quality rate per restaurant. If the preference of a HORECA manager is a passive approach, than pay attention to the importance of visibility and proximity/nearness of providing the toothpicks, and also the hygienic and practical use of single wrapped toothpicks. At last, but not at least, providing of the small boxes of toothpicks in the Indoor Food market was very well appreciated by the costumers, and additionally it seems to encourage their oral selfcare. In general, people are more engaging in Pick a T behaviour if the toothpicks are readily available.

Still further research is needed, especially, in certain ways to make customers and HORECA managers/owners more aware of the importance of such a dental public health intervention; a new implicit and explicit (oral) health related topic in context-related behaviour change circumstances. Moreover, participation in the second pilot study, the survey research may improve customers' oral health knowledge. In addition, the findings of these two pilot Pick a T studies indicate at least a positive short-term impact; it may not only encourage awareness and/or willingness of the HORECA managers/owners to take better care of their own dentition, it may promote interdental cleaning by the use of toothpicks and encourage customers' oral self-care too.

Both pilot studies showed that a population-based, carefully and effectively carried out programs of personal oral self-care may play an important role in the improvement of oral health awareness. Health awareness and increasing knowledge are very important first steps when it comes to behavioural change, and therefore the different phases of the Transtheoretical Model of Behaviour change [13] have to be involved in following oral public health campaign studies. In addition, the use of Intervention Mapping (IM) [14,15] as a protocol for developing theory- based and evidence-based oral health promotion programs is conditional, and further research to refine the effects of this Pick a T campaign or other public awareness campaigns is necessary Finally, from these two Pick a T pilot studies it can be concluded that HORECA organisations are welcome additional contexts to distribute professional toothpicks in order to promote oral selfcare and health behaviour among the public.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Nora Lob, MSc for her valuable professional expertise in the domain of health behavior research, and her help and support in these two Pick a T pilot fieldstudies. Both, we thank Stephany Thijssen for her creative contribution in developing the Pick a T logo and a tailored moodboard. At last, I would like to thank Professor dr. Abraham P. Buunk for his extraordinarily support.

For the first pilot study the single wrapped toothpicks were made available by Jordan®, Lilleborg International, Norway, and for the second pilot the boxes of toothpicks with Aminfluoride were kindly supported study by Colgate-Palmolive Nederland BV, Weesp, The Netherlands.

For more Open Access Journals in Juniper Publishers please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/aboutus.php

For more articles in Open Access Journal of Dentistry & Oral Health please click on:

To know more about Open Access Journals please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/journals.php

Comments

Post a Comment