Community Consultation of Families with Young Children about a New dental Service Centre in Southeast London- Juniper Publishers

Juniper

Publishers-Open Access Journal of Dentistry & Oral Health

Abstract

Objectives: To engage families with

young children and empower them to inform service provision; explore the

views and expectations of families with young children in West Norwood

area of how dental services may be best provided at the West Norwood

Health and Leisure Centre (WNHLC); explore barriers to dental care,

uptake and use of dental services.

Research design: Cross-sectional questionnaire survey

Participants: 1,016 parents/guardians with children aged seven and under.

Main outcome measure: Willingness to access the dental service.

Results:An overall response rate of

24% (246/1016) was achieved. The majority (72%, n=178) were unaware of

the dental services at the Centre. Lack of convenient appointment times

(43%, n=106) was the most common barrier to accessing dental care

reported by families. Approximately 48% of parents indicated their

willingness to bring their children to the WNHLC, the majority of them

were NHS users (75%, n=89, OR=1) who attended the dentist occasionally

(65%, n=77, OR=4.8, p<0.01). Essential facilitating factors were

friendly dental care providers (81%, n=203), ease of getting

appointments (76%, n=186) and suitable opening hours (74%, n=183).

Conclusion: The results of this

study signified the need of collaboration with local settings to

increase awareness about its dental services. The uptake of service

would depend upon factors such as its opening hours, ease of getting

appointments, having a patient-friendly dental team. The results of the

study will inform future dental service provision at the Centre in the

light of NICE guidelines (NICE, 2008).

Keywords: Outreach; Skill-Mix; Access; Barriers; Communication; Dental services; NHSIntroduction

Access to dental services is a major policy and

public concern in the UK, which is considered as “one of the

contributing factors for improvement of oral health”[1,2]. Differences

in oral health and oral health service utilization exist at all levels

for various reasons ranging from psychosocial characteristic of

individuals to regional deprivation [3,4] (Nuttall, Freeman,

Beavan-Seymour, Hill). It is evident from local studies in England that

there is inequity in access in deprived areas of London [5,6,7].

The borough of Lambeth is the fifth most socially and

economically deprived borough in London and distinctive in terms of its

young and dynamic population, ethnic diversity and a highly mobile

population (Census Information Scheme, 2012

&Trust for London and New Policy Institute, 2010-2014). The oral

health needs among pre-school children in local children’s centers are

high [8]. Despite availability of free dental services to children and

more equitable dental services for adults through the National Health

Service in the UK, health service data reveals lower access rates in

Lambeth than London and England [9,10].

Numerous attempts to address inequity in access to

dental services by reorienting dental services to ameliorate oral health

inequalities [11]. The WNHLC is one of the initiatives of the local

authorities in partnership with the NHS to improve health and wellbeing

of the residents in the West Norwood area of south Lambeth (West Norwood

News, 2009). The dental service at the WNHLC provided as a part of

King’s outreach programme, is perceived as an opportunity that will

serve the local community by providing primary dental care in holistic

way

The high need for dental service and low level of service

uptake, as in the West Norwood area, reflects a poor ‘fit’ between

the patient and health care system [12]. Community engagement

in planning, development and management of health related

activities that affect them have been a strategic recommendation.

There is evidence that engaging communities in service design

and delivery empowers them and strengthens community

cohesion making health policy initiatives more sustainable (NICE,

2008). Therefore we set out to assess the families’ perceptions of

barriers in accessing dental services and the factors that would

motivate them to bring their children more often, thus enabling

prevention as well as treatment services [10].

The aim of the project was to explore the views of families

with young children in order to ascertain their expectations of

how dental services may be best provided at the WNHLC, with

a view to informing the structure and delivery of dental services

at this site.

Methods

Chemicals

Ethical approval was granted by King’s College London

Research and Ethics Committee (Ref number BDM/12/13-

77).Based on the local data, children below seven years were

included in the sample [8]. Initially, seven primary schools and

four children’s centres in the West Norwood area from Lambeth’s

Local Authority website [10] within a radius of one mile from the

WNHLC were approached and invited to participate in the study.

Five primary schools and one children’s centre participated and

distributed questionnaires to 1,016 parents and guardians of

children aged five to seven years.

An initial approach with the gatekeepers was made through

a written invitation and promotion was undertaken through

posters and newsletters. The parents/guardians were given the

questionnaire with an information sheet by the class teachers

in an anonymous envelope. The information sheet contained

detailed information about the study and emphasized voluntary

and anonymous participation. Attempts were made to enhance

the response rate by approaching the schools via reminder

letters, emails and phone calls and pens were given as an

incentive and extra questionnaires were kept in each school

(Dillman, Smyth, Christian, 2008).

A two-page questionnaire was derived from validated

questions from the Child’s Dental Health Survey 2003 [3].

Questions on quality of dental care and barriers were derived

from the local surveys [8,13]. The questionnaire consisted of

mainly close-ended questions that derived information about the

awareness of the Centre and its dental service, socio-demographic

features, dental service usage, barriers, preferences, etc. The final

open-ended question requested any suggestions for the dental

service at the Centre. Only 246 parents/guardians returned

completed surveys to their respective class teachers. However,

this number was considered adequate since a calculated sample

size with 80% power at 5% level of significance was 84 to test

the proportion of parents/guardians willing to bring their children, using the chi square test. A multivariate regression

analysis was used to assess factors independently associated

with willingness to bring children to the centre. The regression

model was adjusted for variables such as the awareness of

the WNHLC and its dental service, child’s and respondents’

attendance pattern, child’s and respondents’ type of dental care,

influence of dental students on the respondents’ decision to avail

the service. Quantitative data was analysed using SPSS software

whilst responses to open question were analysed using simple

thematic framework methodology.

Results

Response

Out of the eleven institutions targeted, five primary schools

and one children’s centre agreed to participate in our survey. A

response rate of 24% (range 17% to 80% at school level) was

achieved.

Socio-demographic characteristics as reported by the respondents

The majority of parents (92%, n=225) and children (54%,

n=133) were female. The average age of child was six years

ranging from one to nine years? The presence of siblings was

identified by 32 respondents (12%). In terms of ethnicity, a

majority of the parents identified their children as White (53%,

n=131) followed by Black (21%, n=52) and multiple/mixed

(20%, n=49), Asian (5%, n=11) and other (1%, n=3) ethnic

groups. Here in after, respondents will be referred to as parents.

Reported dental attendance patterns and type of dental care received

In response to questions about dental attendance patterns,

it was reported that 47% parents (n=116) and 64% of their

children (n=158) attended a dentist regularly. A further 31%

parents (n=76) and 25% children (n=61) reported occasionally,

while 20% parents (n=50) and 11% children (n=27) were

reported as attending only when in trouble. There was a

significant association between child and parental attendance

patterns (p<0.001).

When asked about the type of dental service used, out of

246 parents, 71% parents indicated that they received NHS

care (n=174) that was either paid for (40%, n=99) or free (31%,

n=75). On the other hand, a slightly higher proportion of 79%

children (n=193) were reported as being provided NHS dental

care. Furthermore, 17% parents (n=41) utilized private dental

care out of them 40% (n=16) reported utilizing NHS dental care

for their children. A notable proportion of 13% children (n=32)

were reported as utilizing private dental care

Reported awareness about west norwood centre and its dental service

With regards to the awareness of WNHLC, 51% parents

(n=125) were aware about the Centre while the majority (73%,

n=178) had no perception about its dental service as reported.

Of the 125 parents who were aware of the centre, 52% (n=65)

had no knowledge of its dental wing.

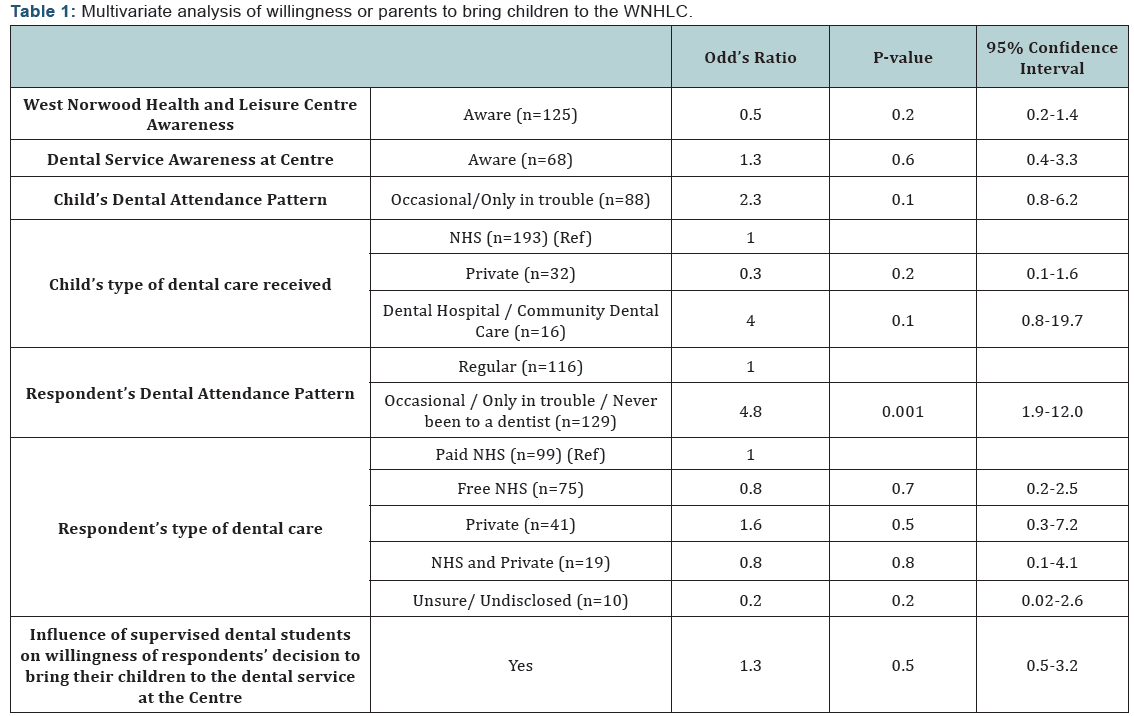

Willingness to bring child to the west norwood centre’s dental service and influence of supervised dental students on decision to bring their child

Overall, 48% (n=119) of parents indicated a willingness to

bring their child to the centre whilst 36% (n=89) were unsure

about the Centre or required more information. Of the 119

parents who reported that they would bring their child, the

dominant ethnic groups were White (46%, n=55), Black (27%,

n=32) and of mixed ethnicity (19%, n=23). The results suggested that among those who showed willingness to bring their child,

75% (n=89) of parents and a higher proportion of 82% children

(n=97) were NHS users. There was significant association

between the child’s ethnicity (p<0.01), child’s dental attendance

(p<0.05) and parental dental attendance (p<0.001) and their

willingness to visit the Centre with Whites, parents and children

attending occasionally or only in trouble identifying that they

were more likely to use the service. Less than half of the parents

(44%, n=107) indicated that the provision of dental treatment by

dental students at the centre would not influence their decision

to visit the Centre as shown in Table 1.

Reported reasons for delay to access dental care for children

The lack of convenient appointment time was the most

important barrier to take their children to the dentist reported

by the parents (43%, n=106). A significant association was found

between lack of convenient appointment time and willingness

of parents to bring their child to the Centre (p<0.01) with the

parents most willing to bring their child to the centre reporting

the lack of convenient appointment time as a barrier to care.

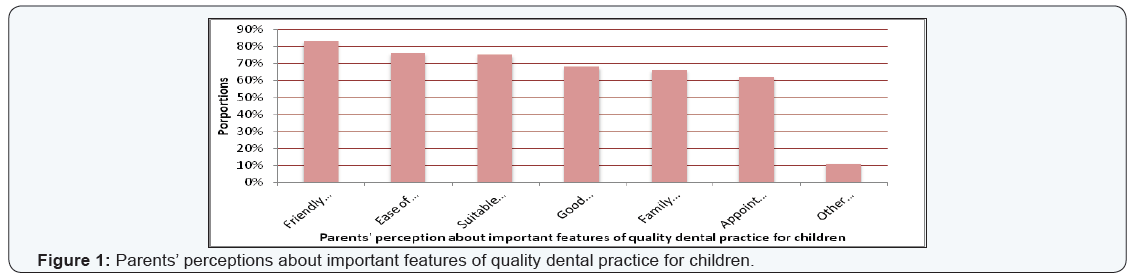

Figure 1 displays responses to what are the important

features of a quality dental service for children. The six key

features showed agreement, having a friendly dental care

provider being the most important issue. Parents were asked

about their preferred time to visit a dentist. The majority of the

parents indicated that after school followed by weekends and

school holidays are the most appropriate times for their children

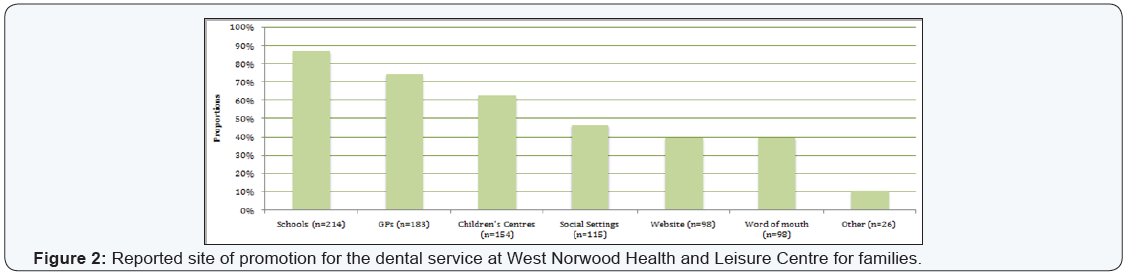

to visit a dentist. The parents were asked to choose from a range

of options on how, and where, the Centre’s dental service could

best promoted the two families in the area who do not have a

dentist. The vast majority of the parents endorsed advertisement

at the schools (87%, n=214) followed by GPs (74%, n=183) and

children’s centres (63%, n=154) as shown in Figure 2.

Parental suggestions

A final question was an open question regarding anything

else the respondents would like to suggest as to how the dental

service at the West Norwood Health and Leisure Centre could

best serve the local families. This accounted to 25% (n=61) of

the total responses.

Maxwell’s dimensions of quality, has been widely used

to evaluate and assess the quality of health services [14]. The

comments and suggestions of parents were in line with Maxwell’s

dimensions. Of all the dimensions of quality, ‘accessibility’ was

predominately evident in the responses. The most repeated

theme that emerged in accessibility were opening hours, ease of

getting appointments, online registration, and special provision

for children with learning disability, advertisement to increase

awareness about the availability of the service in Norwood. In

relation to ‘relevance’ of the dental service, there was a standard

suggestion for the centre to emphasize on preventative services

and oral health awareness through schools and children’s centres

via seminars, workshops, lectures, etc. ‘Acceptability’ mainly was

apparent in terms of accepting supervised dental students as

the primary dental care provider. Areas of concerns regarding

supervised dental students emerged as duration of treatment,

experience in handling children, and change of provider in

every visit, maturity level and confidence linked to anxiety

of respondents. There was a clear demand for transparency

of personnel including need of trained and experienced

supervisors along with a sufficient workforce through means of

dental auxiliaries. Comments in relation to ‘equity’ were raised in relation to acceptance of adults at an affordable rate. The

parents recommended use of patient-friendly aids such as online

booking system, text reminders to increase the ‘effectiveness’

of the dental service. Adequacy of staff was highlighted as an

important criterion to increase the ‘efficiency’ of services.

Discussion

The latest report on Children and Young People’s Health

(2014) recommends improvement in oral health outcomes and reduction in oral health inequalities by putting families with

young children at the heart of commissioning [10]. This study

gave an opportunity to understand the nature of the service

users in terms of socio-demographic characteristics, their

barriers in accessing dental care and the potential areas that

need to be considered in service design and capacity building at

the new centre.

In this study, the majority of the respondents were females.

The gender profile of the children in the study sample was

identical to Lambeth’s general children population with 51%

female and 48% male (Lambeth First 2011). In terms of ethnicity,

the sample showed similar characteristics to the Lambeth

population with the maximum number of respondents classifying

themselves as ‘white’ followed by ‘black’ and ‘multiple’ ethnic

groups. The willingness to use the new centre showed variations

with respect to ethnicity, respondents classifying themselves as

‘white’ being more willing to use the dental service at the new

centre.

The majority of the parents and their children were users of

the NHS dental care, which were similar to the results from the

national survey. Additionally, similarity in results to the national

surveys was evident in terms of dental attendance patterns;

the majority of the parents and their children reported visiting

their dentists for regular check-ups (Morris et al. 2006; Office

for National Statistics 2011). This finding may be a result of

response bias as a questionnaire approach may have filtered

out the ones who are less likely to visit a dentist or respond

to a survey because evidence suggests that Lambeth has low

uptake of dental care [6, 8-10]. There could also be two other

possibilities in that the questionnaire attracted pro-active

parents or the parents genuinely attend the dentist regularly as

reported (Benett 2013).

Parental and child’s attendance patterns were seen to be

strongly associated with each other which is similar to findings

from the national survey (Morris et al. 2006). As reported by

other studies, in this population the parental perception of dental need predicted their dental attendance [15,16]. This

study also showed that there was an association between

parents’ attendance pattern and their willingness to bring

their child to the new centre’s dental service. Those being nonregular

attenders reported they were more likely to use the

dental service at the centre. This may have an positive impact

on reducing oral health inequalities as evidence shows that oral

health and associated problems are associated with attendance

pattern [17] (Richards & Ameen 2002).

This study showed that, according to their parents, the

majority of children were reported to have had no recent dental

problem. These findings do not necessarily suggest absence of

dental problems but may be a result of ‘social desirability’ or lack

of awareness of the child’s oral health as highlighted in previous

studies [13] (Sjöström & Holst 2002).

A significant relation between the age of the child and

the time since the last dental visit was observed, which was

more pronounced in the 5-7 age groups. Various reasons may

contribute to this finding. One may be that decay in deciduous

molars is more common in this age group as highlighted in other

studies (Levine, Pitts, Nugent 2002; Milsom, Blinkhorn, Tickle

2008).

In terms of barriers to access to dental care for their children,

the study highlighted that lack of convenient appointment

times was the most common difficulty faced by the parents. In

addition, parents being busy, failure to find a dentist followed by

fear of cost were also found to hinder the use of dental service.

These findings confirm results from previous researches done in

the area [5,8,13,18]. In response to the most convenient time to

bring their children, there was a definite preference of having

appointments after school, at weekends and during school

holidays. Finally, in terms of defining a quality dental practice for

children, it was found that a child-friendly dental care provider

with ease of getting appointments and suitable opening hours

are important factors that need to be considered, which are in

parallel to previous research evidence [19,20].

With regards to dental care being provided by dental

students, there was a mixed response with less than half of the

parents approving the concept, which was similar to the findings

of another recent local study [19]. Suggestions in terms of

necessity of mandatory supervision of the students along with

issues linked to the experience and level of expertise were made.

The barriers as well as preferences suggested by the

parents

are key features that need to be considered while planning

the service delivery at the new centre. An area that will need

to be clarified is the discrepancy between preferred time for

appointments and the working hours of the dental students.

Traditionally dental students have provided care during normal

9-5 office hours, Monday to Friday. It should also be born in mind

that after school is not always the best time to treat children

as they may be tired after a day at school. However, Saturday

opening may also be a consideration as the health and wellbeing centre

will be open seven days a week (Swider & Valukas 2004).

Furthermore, awareness of the centre and its dental services

was relatively low. However, it may be suggested that this study

might have had the positive effect of raising awareness of the

dental service at the centre amongst the parents who had no

previous knowledge of it. There is a need to initiate collaboration

between the Centre and the local settings such as schools, general

practitioners (GPs) and children’s centres in order to promote

the centre.

There were a number of limitations encountered during the

study. Feedback from the ethics committee suggested that ‘any

identifiable information (e.g. post code) should not be considered

in the survey to protect anonymity’. Indeed the previous study in

West Norwood found that taking the post code information from

participants did not benefit the overall study [19]. It should be

born in mind however that it is recognised that socio-economic

disparities are evident in oral health and related issues and any

bias in this area would not be detectable. The study design initially

included a qualitative approach using interviews/focus groups

that would have been ideal to explore the views and expectations

of families with young children but the schools found it difficult

to implement them (Ritchie, Lewis, Nicholls, Ormston, 2013).

The cross sectional self-administered questionnaire approach

featured a response rate of 24%, which varied between schools.

The fairly low response rate may introduce ‘non-responder’ bias

and could be a result of the lack of knowledge of the proposed

service (Berg 2005). Despite attempts to engage with the schools

and children’s centres and increase response rates by displaying

posters and putting up a note in the school newsletter as well as

a pen as incentive (Dillman et al. 2008; Edwards, et al. 2002), the

engagement of parents and guardians through the schools was

questionable.

Response bias was minimised by formatting the

questionnaires as suggested by William (2003) that included

non-leading, non-ambiguous simple and short questions,

the page-layout and clarity of the questionnaire. It has been

suggested that respondents often answer according to the social

norms prevailing rather than the factual situation and hence

social desirability might be a factor that may bias the results of

questionnaire surveys (Sjöström & Holst 2002). Also, the study

had a majority of females and it has been observed in national

data that women are more likely to report accessing dental care

than men (Office for National Statistics 2011). However, the

semi-structured questionnaire design had many advantages and

produced 246 responses that gave an opportunity to explore

various areas. It also provided the parents, an opportunity to

provide anonymously suggestions for future dental service

provision.

This research was one of its kind in informing future

actions

to ensure that West Norwood Health and Leisure Centre’s

Dental Service, serves the local population and maximises the

acceptability and utilisation of the service by catering services with

service user involvement. The ‘White Paper (2010)’ in their

slogan (No decision about me, without me) mentions that the

consumers of services should be the heart of everything and

in charge of decision-making about their care. Perhaps, if the

suggestions were implemented, measuring the outcomes could

add to the predictability of such a contemporary approach.

Conclusion

The study suggests that the awareness of parents/guardians

using the West Norwood Dental Services would increase if

the Centre promotes itself and collaborates with schools and

children’s centres and GPs. The results of the study show that

uptake of dental service would depend upon factors such as

opening hours, ease of getting appointments especially after

school and weekends, having a friendly dental team in a child

friendly dental setting. This study provided evidence that parents

of young children whose patterns of dental attendance are

less than ideal may be more interested in attending the centre.

The results of the study will inform dental service provision

at the West Norwood Health and Leisure Centre, although

implementing the findings may be challenging and will require

inter-sectorial co-operation.

For more Open Access Journals in Juniper Publishers please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com

For more articles in Open Access Journal of Dentistry & Oral Health please click on:

Comments

Post a Comment